The Arab Jews I

The histories of Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews in the Arab world and Israel.

The history of Arab Jews, particularly Mizrahi Jewish communities, is one of cultural exchange, coexistence, and resilience within the Arab world. For centuries, these communities flourished alongside their Muslim and Christian neighbours, deeply embedding themselves in the languages, traditions, and landscapes of their homelands. However, the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 marked a significant turning point for many Mizrahi Jews, as they were drawn into the Zionist project amidst a blend of hope, pressure, and controversy. In this article, we explore their migration to Israel, the factors behind it, and their vital role in shaping it. I will later also touch upon other aspects.

The Establishment of Israel

When Israel was founded in 1948, it was largely established by European Jews, often referred to as Ashkenazi Jews. Many of these Jews were Holocaust survivors who had experienced the horrors of World War II. For them, Israel symbolised a refuge and a new beginning—a place to build a homeland after facing persecution and displacement. The creation of a functioning state, however, was a monumental task. Infrastructure, agriculture, industry, and governance all had to be developed simultaneously, making the task complex and overwhelming.

In the newly established state, a range of roles needed to be filled to support the development of society. Israel required workers for farms, factories, and construction projects, along with people to populate newly built towns and settlements. These labour-intensive tasks were essential for the country’s growth but were often physically demanding and not highly regarded. Meanwhile, many Ashkenazi Jews, due to their educational and cultural backgrounds, sought leadership and administrative positions in government, industry, and the military. This created a dilemma —who would fill the lower-status but crucial roles?

The Labour Shortage

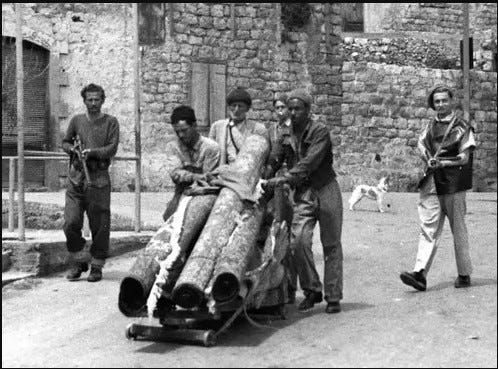

To address this issue, Israel turned to Jewish communities from Arab and North African countries, known as Mizrahi or Sephardi Jews. These communities were encouraged, and in some cases pressured, to immigrate to Israel to help fill the necessary workforce. While their arrival helped alleviate labour shortages, their migration and integration were fraught with difficulties. Many newcomers found themselves assigned to less desirable jobs and areas, often located far from urban centres where power and opportunities were concentrated. This situation set the stage for social and economic divisions that would influence Israeli society for years to come.

To address the labour shortage, Israel turned to Jewish communities from Arab and North African countries, collectively referred to as Mizrahi or Sephardi Jews. These communities, with their rich histories and deep-rooted traditions, were encouraged to immigrate to Israel as part of the state-building process. The Israeli government employed a combination of incentives and subtle pressure to facilitate this migration, emphasizing the need for manpower in the fledgling state.

In some instances, more controversial measures were undertaken. For example, the Lavon Affair, a failed false flag operation carried out by Israeli operatives in Egypt, sought to influence political conditions to favour Israeli interests. Similarly, the Baghdad bombings—allegedly orchestrated by Zionist agents—were reportedly aimed at accelerating the exodus of Iraqi Jews. Unlike the Lavon Affair, the Baghdad bombings were ultimately successful, though their exact origins remain the subject of debate among historians.

Integration Challenges

When Mizrahi Jews moved to Israel, their immigration was seen as a way to grow the population and fill the need for workers. However, despite promises of a better life, many faced serious challenges. They dealt with cultural differences, poverty, and unfair treatment in society. Mizrahi Jews were often given tough, low-paying jobs in farming, construction, and factories. While these jobs were important for Israel's growth, they didn’t offer much chance to move up socially or economically. On top of this, many Mizrahi families were sent to live in remote areas far from the main cities. These places often lacked good infrastructure and opportunities, making it harder for them to thrive.

Being pushed into certain jobs and areas created deep divisions in Israeli society. Power and privilege were centred in the cities and held mainly by Ashkenazi Jews, leaving Mizrahi Jews feeling like second-class citizens. Over time, this led to feelings of frustration and resentment, which added to tensions in society. These divides, based on ethnicity and social class, became deeply rooted and shaped Israeli society for years to come.

The Distinction Between Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews

The term Mizrahi, meaning "Eastern" in Hebrew, typically refers to Jews from the Middle East and North Africa, such as those from Iraq, Yemen, Syria, and Morocco. The term Sephardi, on the other hand, traditionally refers to Jews of Spanish and Portuguese descent who were expelled during the Inquisition and later settled in the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, and other parts of the Middle East. Over time, the distinctions between these groups became blurred, as both Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews shared cultural and religious practices influenced by their lives in Islamic societies.

Their languages, cuisines, and religious customs created a shared cultural experience, despite the distinct historical origins of the two groups. In Israel, Mizrahi has come to be used as a broad label for both groups, reflecting their shared experiences of marginalisation and discrimination in the new state. I will continue to explore this history in The Arab Jews II.

All articles on Diaspora Dialogue are free to read for one year from publication. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and would like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing, or by buying me a coffee. Thank you for reading and being part of the dialogue!

Looking forward to part 2. I read Avi Shlaim’s autobiography last year on his experiences of growing in Baghdad and the dislocations he felt moving to Israel. Also a subscriber to Alon Mizrahi’s Substack.

Very informative, I have always wondered what an 'ashkenazi' jew was. Sorry bout spelling. Looking forward to Part 2. Thank you.