Arab Jews II

Understanding Palestinian Jews and Their Distinct Identity

In my previous article, I talked about the Arab Jews in general and the experiences of Jewish communities from Arab lands. In this follow-up, I’ll look closer at the Palestinian Jews—a group often associated with Mizrahi Jews yet possessing a unique history and identity. Similarly, Jews from Morocco, Iraq, and Yemen also have distinct identities shaped by their specific cultural and historical contexts and different from each other. However, as these communities converged in Palestine, the Palestinian Jews stand out as particularly significant due to their deep-rooted connection to the land and its people. This article will delve into their unique cultural roots, their place within the broader Mizrahi framework, and how these identities have influenced their experiences.

Who Were Palestinian Jews?

Before the establishment of Israel in 1948, a Jewish community had lived in Palestine for centuries. In the 19th century, the collective Jewish communities of Ottoman Syria and later Mandatory Palestine were commonly referred to as the Yishuv. This term is divided into two categories: the New Yishuv and the Old Yishuv. The New Yishuv largely consisted of Jews who immigrated to the Levant during waves of Jewish migration, beginning with the First Aliyah (1881–1903). "Aliyah" refers to the act of Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel, regarded in Jewish tradition as an important and spiritually significant act. The Old Yishuv, by contrast, encompassed the Palestinian Jewish community that had been established in the region prior to these migrations and the rise of Zionism.

In a previous post about Palestinian cuisine, I discussed the topic of cultural appropriation, and I realise my phrasing could have been more precise. The Old Yishuv, which was part of the Jewish community, shared commonalities in cuisine, culture, language, and traditions with their Muslim and Christian Palestinian neighbours. These Jews were not immigrants but had deep, long-standing ties to the region, forming an integral part of the broader Arab society and, more specifically, the Palestinian community. Many Palestinian Jews identified as both Arabs and Palestinians, seeing themselves as a crucial part of the local community.

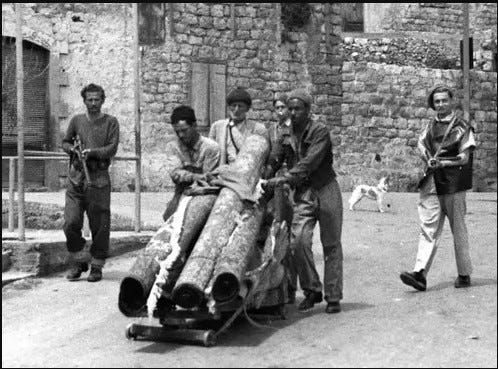

Like their Arab neighbours, these Jews spoke Arabic in their daily lives. They observed similar customs and practiced shared cultural traditions. Many were involved in trade, farming, and crafts, contributing significantly to the local economy and culture. Their identity was deeply connected to the land and the surrounding Arab community.

The Impact of Zionism on Palestinian Jews

With the rise of Zionism and the establishment of Israel in 1948, the situation for Palestinian Jews changed. The creation of a Jewish state in Palestine led to the displacement of many Palestinian Arabs, including the Jewish communities living there. After the founding of Israel, some Palestinian Jews chose to remain in the new state, while others left or were forced to leave due to the changing political and social environment.

Zionist policies aimed to create a unified Jewish identity that aligned with the idea of a modern, European-inspired Jewish state. As part of this project, many Arab Jewish communities, including Palestinian Jews, were “encouraged” to blend into the larger Israeli society. In this new Israeli context, their distinct Palestinian Arab identity was often overlooked, suppressed or erased, as it didn't fit into the Zionist narrative.

Palestinian Jews and Mizrahi Identity

While Palestinian Jews shared deep cultural and historical ties with their Arab neighbours, the term Mizrahi (meaning “Eastern”) was applied to Jews from broader Middle Eastern and North African regions. Mizrahi Jews often hailed from countries such as Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Morocco, and Tunisia, and were categorized as “Eastern Jews” in contrast to their European (Ashkenazi) counterparts.

However, Palestinian Jews occupied a unique position within the Arab world. Their history and identity were deeply rooted in Palestine itself, and the term Mizrahi fails to capture the full complexities of their experience. Using this label risks erasing their distinct connection to the land and their integral role in the shared history of Palestinians. Issues of discrimination against Mizrahi Jews and their subsequent political movements also form an important part of this story. I plan to explore these topics further in The Arab Jews III.

All articles on Diaspora Dialogue are free to read for one year from publication. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and would like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing, or by buying me a coffee. Thank you for reading and being part of the dialogue!