In the first three parts of this series, we explored the histories, identities, and challenges faced by Mizrahi Jews—those with roots in the Arab and Muslim world. We looked at their migration to Israel, the loss of their Arab identity, and the discrimination they experienced. In this fourth part, we revisit the potential unity between Mizrahi Jews and Palestinians, examining how this solidarity was undermined by Zionist policies, and how, over time, many Mizrahim abandoned left-wing Zionism to embrace the far-right.

While researching for this piece, I came across a Vox article by Sigal Samuel that showed this solidarity movement did indeed exist, albeit briefly, and was crushed by Israeli state policies. This is why I love writing and digging for more information—there’s always something new to learn. This discovery deepened my understanding of the Mizrahi experience. The article is definitely worth reading!

Mizrahi Solidarity with Palestinians

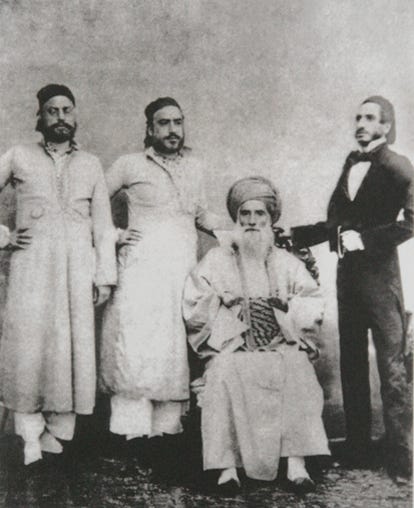

Historically, Mizrahi Jews lived harmoniously in the Arab world, but their identity was challenged with the establishment of Israel. Many Mizrahi thinkers, witnessing the discrimination they faced in Israel, recognized parallels with the treatment of Palestinians. They shared in the experiences of Orientalism—the idea that “Eastern” cultures are inferior to Western ones. Edward Said’s framework helped explain how both Mizrahim and Palestinians were seen as “uncivilized” by the predominantly Ashkenazi society.

In the 1950s, Mizrahim and Palestinians attempted to form solidarity through protests and media outlets, advocating for justice. This movement, however, was quashed by Israeli authorities, who utilized force and divisive policies to prevent any real cooperation between the two groups. A combination of racial prejudice and the Zionist vision of Jewish exceptionalism created a wedge between Mizrahim and Palestinians that proved difficult to bridge.

The Shift to the Far Right

By the 1970s, as Mizrahim’s socioeconomic conditions remained grim, they were increasingly drawn to Israel’s right-wing political parties. The struggle for social equality, which initially aligned them with the left, began to shift as right-wing parties such as Likud started to represent their grievances. Key to this shift was the appeal of a nationalist, often anti-Arab, narrative that promised economic advancement and political power.

The change in Mizrahi political alignment, particularly among their children, is a response to decades of systemic discrimination and frustration. Many felt abandoned by the left-wing Zionists and instead found resonance in a far-right ideology that emphasized a strong Jewish identity. The increasing rhetoric of nationalism and security became attractive as a way of asserting Mizrahi belonging in a society that had often marginalized them.

This political shift can be attributed to a combination of economic hardship, cultural alienation, and the erosion of solidarity between Mizrahim and Palestinians. As the state pushed for an increasingly exclusionary, nationalist identity, Mizrahim were socialized into the far-right vision, which framed Palestinians as the enemy rather than potential allies in the fight against common oppression.

Losing Identity and Embracing Nationalism

The term "Mizrahi" itself reveals the systematic erasure of Arab identity. In Israel, Mizrahi Jews were pressured to abandon their Arab heritage—Arabic language, culture, and traditions—and adopt a more Westernized, Zionist identity. This cultural erasure was designed to make them into loyal citizens of the new state but also rendered them complicit in the marginalization of Palestinian Arabs, reinforcing the divide between the two groups.

Over time, many Mizrahim, especially their children, embraced a Zionist narrative that defined them in opposition to the Arab world, rather than as part of it. Leaders like Theodor Herzl and later figures such as Benjamin Netanyahu reinforced the idea that Israel was a “villa in the jungle,” a beacon of Western civilization surrounded by a “barbaric” Arab world. This mindset was internalized by Mizrahim, many of whom turned to the far-right as the vehicle through which they could secure their place in the Israeli social order.

The Road Not Taken

The potential for Mizrahi-Palestinian solidarity was buried beneath decades of government policy and a growing societal division. Figures like Eliyahu Eliachar and Latif Dori advocated for unity, calling for a society that embraced both Jewish and Arab identities. However, these voices were drowned out by the state’s growing investment in a monolithic, exclusionary Jewish identity. Mizrahi political participation, increasingly aligned with right-wing parties.

This shift to the far right, exemplified by the embrace of nationalist rhetoric, has had a lasting impact on Israeli politics. The rise of parties like Likud and the strengthening of religious-right movements have enabled a vision of Israel that prioritizes Jewish hegemony over coexistence. Mizrahim, who once sought solidarity with Palestinians, now form a key voting bloc for the very forces that perpetuate the state’s discrimination against them and the Palestinians.

Conclusion

The story of Mizrahi Jews in Israel is one of loss—of culture, identity, and solidarity. The rise of the far-right is both a consequence and a reflection of decades of cultural erasure, political disillusionment, and systemic oppression. In reflecting on the history of Mizrahi Jews, it is clear that Israel’s political landscape has been shaped by the interplay of exclusion and assimilation.

A few last words: I got a question about the Arab Jews from Juel Meyer, and the answer to that will be in The Arab Jews V. However, I’ve got a few other articles to finish up first, but I’ll be back to this soon!