On my second article in the series about the Arab Jews, I received a question from

.The answer became quite long, and ended in this article. It would be inaccurate to say that Jews in Ottoman Palestine identified as "Palestinians" in the modern national sense. That term, as we understand it today, did not yet exist as a distinct political identity. My earlier statement that "Many Palestinian Jews identified as both Arabs and Palestinians, seeing themselves as a crucial part of the local community" was an attempt to emphasize their deep integration into the local society. However, while native Jews were very much part of the cultural and social fabric of the region, they did not conceive of themselves in the national categories that would later emerge, and neither did anyone else.

For centuries, Jewish communities lived as part of the broader Arab world, speaking Arabic, engaging in local customs, and sharing a deep connection with their Muslim and Christian neighbors. These communities, often called "Arab Jews," were not a separate nation but an integral part of the diverse societies they lived in. In Ottoman Palestine, this reality was particularly strong, as native Jewish communities were deeply embedded in the local Arab cultural world. However, as modern nationalism rose and Zionism reshaped Jewish identity, these long-standing connections were gradually severed.

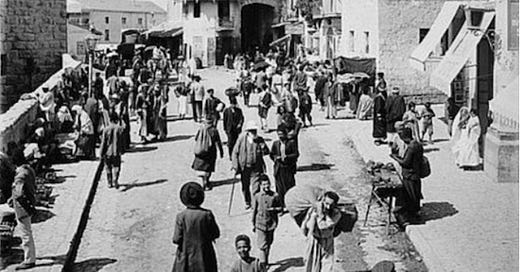

Living in a Shared Culture

During the Ottoman era, the people of Palestine—Muslims, Christians, and Jews—lived together in a society where identity was defined more by language, culture, and local ties than by national labels. Native Jews, whether speaking Arabic or Judeo-Spanish (Ladino), were often referred to as "Abna' al-Balad" (sons of the country/soil) by their Arab neighbors. This term reflected their status as indigenous inhabitants who belonged to the land alongside other Palestinians.

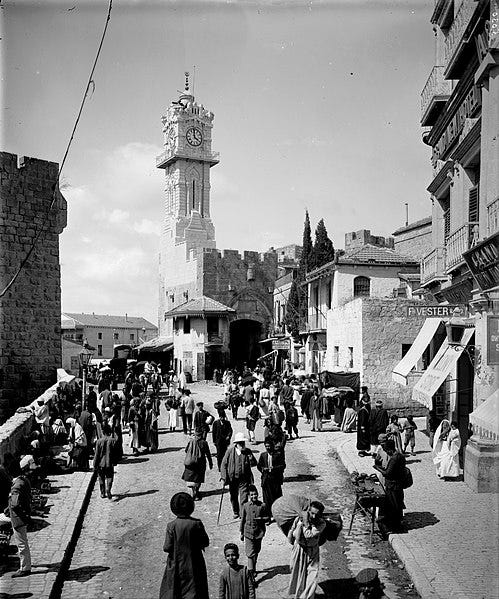

Jews in cities like Jerusalem, Hebron, Safad, and Tiberias participated in communal life alongside Muslims and Christians. They traded in the markets, attended local schools, and engaged in shared religious customs. Arabic was a common language among these communities, and many Jewish scholars wrote in Arabic, contributing to the intellectual and literary life of the region. The idea of "Jew" and "Arab" as rigidly separate identities did not exist in the way it does today.

Everyday Connections and Social Life

Social interactions between Jews and their Arab neighbors were not limited to business and trade. There were deep cultural exchanges. For example, Jewish families in Jerusalem and Hebron often shared traditional foods with their Muslim neighbors during holidays, and vice versa. Jews and Muslims celebrated religious festivals side by side, reinforcing the sense of a shared community.

Even within education, Arabic played a central role. Many native Jews attended Ottoman public schools where instruction was given in Arabic which offered education to Jewish, Christian and Muslim students. This fostered a sense of coexistence and common belonging.

The Impact of Zionism and Changing Identities

The arrival of European Jewish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought a shift in the way Jewish identity was understood in Palestine. These new immigrants, largely Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, brought with them the Zionist movement—a political project aiming to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. While many native Jews initially supported Zionism as a means of modernization, the movement increasingly promoted a distinct Jewish national identity that separated Jews from their Arab surroundings.

As Zionist policies encouraged European Jews to settle in Palestine, native Jews were pressured to abandon their Arab cultural ties. Arabic-speaking Jews were gradually rebranded as "Mizrahi" (Eastern) Jews, a term that distanced them from their Arab roots and grouped them into a category distinct from both Ashkenazi Jews and Palestinian Arabs.

One visible sign of this shift was in urban geography. Many native Jews moved from the Old City of Jerusalem—where they had lived among Arabs—to newly built Jewish-only neighborhoods. The revival of Hebrew as a spoken language further pushed Arabic into the background.

The transformation was not immediate, but over time, the deep historical connection between Arab Jews and their surroundings was replaced with a new identity—one that framed them as part of a separate, Western-oriented Jewish nation rather than a natural part of the Arab world.

How Arab Jews Became "Mizrahi"

This transformation was not just about language or place—it was also about memory and self-definition. The Zionist movement promoted the idea that Jews had been disconnected from the Middle East for centuries and were now "returning" to their homeland. This idea overlooked the reality that Arab Jews had never left; they had always been part of the region's history.

As Jewish nationalism grew stronger, Arab Jewish heritage was de-emphasized, and Mizrahi Jews were encouraged to see themselves as part of a broader Jewish people rather than as Arabs of Jewish faith. This redefinition was reinforced by state policies, social pressure, and even military service, where Hebrew became the dominant language and European customs were prioritized.

Conclusion

Before the rise of modern nationalism and Zionism, the identities of Jews in Ottoman Palestine were not fixed in the way they are today. Many native Jews saw themselves as part of an Arab cultural world. They spoke Arabic, engaged in Arab customs, and were fully integrated into local society. The shift away from this identity was not natural; it was a product of political changes and the efforts of Zionist leaders to reshape Jewish identity into a nationalistic framework.

Today, as more scholars and activists revisit the history of Arab Jews, there is a growing awareness of this lost heritage. Understanding that Jewish and Arab identities were once deeply intertwined challenges modern assumptions and opens the door for new ways of thinking about coexistence and shared history.

The story of Arab Jews in Palestine is one of deep connection, cultural exchange, and ultimately, loss. Before the rise of Zionism, many Jews in Ottoman Palestine were seen as part of the Arab world, sharing language, traditions, and everyday life with their Muslim and Christian neighbors. Over time, these ties were broken, and Arab Jews were given a new identity as "Mizrahi," separating them from their roots.

Looking back at this history reminds us that identities are not fixed; they are shaped by political and social forces. The Arab Jewish experience challenges the modern view that Jews and Arabs have always been separate and offers a different vision—one where people of different faiths lived together, shared culture, and saw each other as part of the same land.

The sources referenced in this article and the previous ones in this series come from a combination of recent research and longer-term readings. Over the past few months, I’ve engaged more deeply with works such as Salim Tamari's “Ishaq al-Shami and the Predicament of the Arab Jew in Palestine” (Jerusalem Quarterly), Ella Shohat's “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims,” Menachem Klein's Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron, Shohat's “The Invention of the Mizrahim,” and Yehouda Shenhav's The Arab Jews: A Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity. In addition to these recent studies, much of my understanding has been shaped by insights gathered over many years, including conversations with a Palestinian elder and other sources that have helped shape my perspective on this topic.

All articles on Diaspora Dialogue are free to read for one year from publication. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and would like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing, or by buying me a coffee. Thank you for reading and being part of the dialogue!

Great article Shoaib. Joel Meyer's questioning seems quite divisive to me. What he is alluding to is that he doesn't think the people of Palestine identified as being Palestinian...