The Village Under the Forest (2013)

Uncovering the Past Beneath the Pines - Weaponized Landscape

The Village Under the Forest is a 2013 documentary directed by Mark J. Kaplan and written by Heidi Grunebaum. The film explores how Israel displaced Palestinians in 1948 and subsequently concealed their existence by planting forests over the remains of destroyed Palestinian villages. Specifically, it focuses on the Jewish National Fund (JNF) forest named The South Africa Forest, which was planted over the ruins of the Palestinian village of Lubya, destroyed during the Nakba.

The Role of the JNF

The JNF is an international Zionist organisation, and it holds semi-governmental authority in Israel today. Established in 1901 as one of the earliest Zionist institutions, its primary mission was to acquire and develop land for Jewish settlement in what was then Ottoman-ruled Palestine, later the British Mandate of Palestine. Historically, the JNF operated under bylaws that restricting land sales exclusively to Jews, reflecting its founding goals.

Over the years, this practice has drawn criticism and legal challenges, leading to some policy changes. However, the majority of JNF land is still leased rather than sold outright. For decades, the organisation raised funds primarily from Jewish communities in Europe and North America, using its iconic Blue Boxes to promote the idea that their contributions would help "make the desert bloom." However, The Village Under the Forest reveals that these efforts were not only about land development; they were also about erasing Palestinian history.

Forests as Tools of Erasure

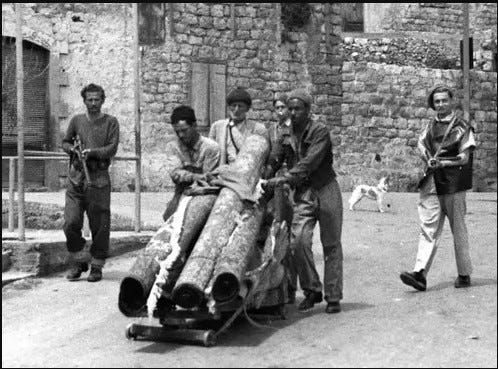

In the 1950s and 1960s, vast areas of land were planted with JNF pine forests. This effort was not only aimed at "reclaiming" the land but also at concealing the remnants of recent Palestinian history. The land, still seen as too “Arabic”, needed transformation. While the founders of Israel publicly focused on uncovering traces of ancient Jewish civilizations through archaeology, they simultaneously worked to obscure the more recent history of the land—specifically, the ruins of Palestinian villages destroyed during the Nakba. These forested tracts served a dual purpose: to enforce the new Israeli narrative and to obscure the war crimes that marked the state's founding.

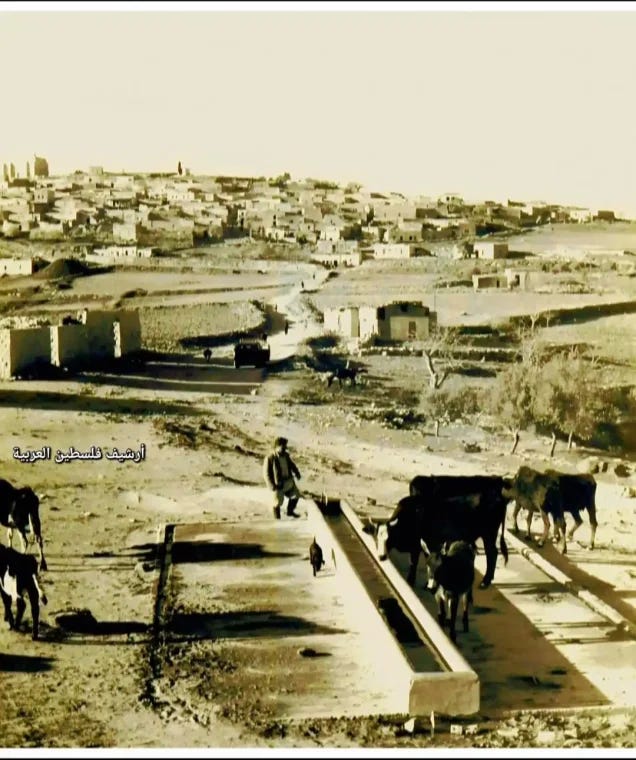

One such example, highlighted in the film, is the Arab-Palestinian town of Lubya. Before 1948, Lubya was a thriving community of 2,350 residents. Today, the site is part of the South Africa Forest. But it is far from the only example. Many of the approximately 400 Palestinian towns and villages destroyed or depopulated during the Nakba now lie beneath forests planted by JNF, in the movie they say its 86 JNF forests which are planted over arab villages. These afforestation efforts were not only about ecological restoration but also about covering up the remnants of Palestinian villages, both physically and symbolically, making it more difficult to trace the historical presence of Palestinian communities in those areas. Other villages were built over and given Hebrew names; the tactic may have differed, but the goal remained the same: to erase and change the history of the land.

A Film of Contrasts and Revelations

The technical aspects of The Village Under the Forest are well-crafted, employing a mix of archival footage, poetic narration, and present-day visuals of the forest that conceals Lubya. The narration is reflective and intimate, providing a strong emotional core to the story. The film’s use of historical documents, maps, and interviews with survivors and experts adds depth and credibility to its narrative. Particularly effective are the scenes showing the forest as it stands today—seemingly peaceful but holding layers of hidden trauma. The contrast between the beauty of the forest and the painful history it hides is both poignant and unsettling.

The village under the forest is a striking example of how the landscape itself was reshaped to erase traces of its Arab past. The JNF deliberately planted European pine trees over the site of an Arab village, attempting to cover up its history and transform the area into something new and different. This act of environmental manipulation can be seen as symbolic of broader efforts to displace the Arab identity of the land and replace it with a Jewish one. By introducing non-native species like European pine trees, the JNF not only redefined the physical appearance of the land but also sought to plant a new, European Jewish narrative into the very soil of Palestine.

This symbolic planting, alongside the physical reorganization of the landscape, asserted a new identity—one that distanced itself from the Arab roots of the land. In this way, the European pine trees became more than just a tool of land reclamation; they embodied the larger cultural and ideological shift that sought to transplant European Jewish roots into historically Arab soil.

Call to Remember

Like Tantura, the movie I reviewed last week, The Village Under the Forest reveals that what we see on the surface is often far from the truth. The forests, today framed as environmental projects, are, in fact, monuments to erasure—designed to obscure the violent history of displacement and destruction. In recent years, the justification for these projects has increasingly relied on environmental arguments. By promoting afforestation as a means of ecological preservation or improvement, organizations like the JNF obscure their true intent: to rewrite history and erase Palestine's Arab past. This shift in narrative aligns these efforts with globally valued causes, masking the erasure as a virtuous act rather than a tool of oppression.

This film is much more of a personal journey than Tantura. We follow Heidi as a young girl visiting the forest, contributing to afforestation efforts, unaware of the history hidden beneath the forest floor, and learning about the propaganda surrounding the 1948 war. Now, as an adult with knowledge and understanding, she returns to explore more of this history. Interwoven with the history of her birthplace, South Africa—also suffering under apartheid—she draws parallels between the two struggles. The film also features numerous experts, providing historical context. We learn that forests in various countries, including my own, Norway, were part of this effort. It makes me wonder whether the Norwegian forests might also be concealing a massacre or a village razed to the ground. Other countries that contributed to the afforestation efforts mentioned in the film include the USA, Canada, Australia, Britain, Germany, Sweden, Italy, Denmark, France, Switzerland, Bolivia, Argentina, and Venezuela. For many of those contributing, they probably believed, as Heidi once did, that this effort was about making the desert bloom, rather than erasing Palestinian history.

Conclusion

The Village Under the Forest is not just a film about the past but a call to remember, uncover, and hold accountable those who erase histories for their own narratives. It serves as a sobering reminder that the scars of 1948 are still visible, even if hidden beneath layers of pine trees. It's about daring to see through propaganda and seeking the truth, even when it feels uncomfortable. It’s about standing up for what’s right.

This movie strives to cover a lot in under an hour and succeeds in many aspects. However, it mentions several points in passing that require further reading to fully understand. I’m happy to say that much of this is explored in my own series of articles here. It’s not only a historical account but also a deeply personal story, and it is definitely worth watching.

All articles on Diaspora Dialogue are free to read for one year from publication. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and would like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing, or by buying me a coffee. Thank you for reading and being part of the dialogue!

I think Kamala Harris spoke about the blue boxes as a found memory of her youth?

As a Swedish citizen I remember that we had visitors from ”Israel” in my school, in the late 70’s(?). I don’t recall everything but they showed us pictures of their communities and I suppose they were in the process of doing PR for the occupation.