It’s a narrative that resurfaces often in discussions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Palestinians could have had their own state in 1948 but “chose not to.” On the surface, this argument seems straightforward—a neat explanation for a protracted conflict. But history rarely conforms to such tidy interpretations, and this narrative distorts the complexities of 1948 while unfairly placing the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Palestinians.

A Deeply Unfair Partition

The story begins with the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan, which proposed dividing Mandatory Palestine into two states: one for Jews and one for Arabs, with Jerusalem under international administration. While this plan ostensibly offered a solution, it was deeply skewed. Despite comprising only about one-third of the population and owning less than 10% of the land, the Jewish state was allocated 56% of the territory. For Palestinians, the majority population, this was not a plan for coexistence; it was a mandate for dispossession.

Unsurprisingly, Palestinians rejected the partition. But their refusal wasn’t about rejecting statehood; it was about rejecting an imposed solution that ignored their demographic majority and historical ties to the land.

The Path to Displacement

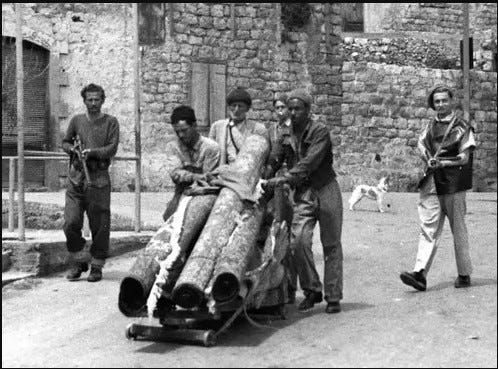

When critics claim Palestinians could have had a state in 1948, they often overlook the violence and dispossession that preceded Israel’s declaration of independence. The massacre at Deir Yassin on April 9, 1948, just weeks before the declaration of Israeli independence, marked a key turning point. Over 100 Palestinian civilians were killed by Zionist paramilitary groups in an attack that sent shockwaves through Palestinian society. This massacre was not an isolated incident but part of a broader campaign of intimidation and displacement. Villages were emptied, homes destroyed, and entire communities forced to flee in fear of similar atrocities.

By the time Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians had already been displaced, and the groundwork for what would become the Nakba (“the catastrophe”) was well underway. How could a people agree to a partition plan when the reality on the ground was one of violence, destruction, and forced expulsion? This wasn’t a negotiation between equals; it was a scenario in which one side had international support and military strength, while the other was grappling with fragmentation and survival.

Arab States: Pressured by the Streets and Fragmented in Strategy

The involvement of Arab states in the 1948 war is often cited as a reason for the failure to establish a Palestinian state. While Arab armies did intervene, their actions were not solely driven by geopolitical ambitions. There was significant pressure from the “Arab street,” where reports of massacres like Deir Yassin and the mass displacement of Palestinians had sparked outrage.

Public anger over the suffering of Palestinians created a groundswell of demand for action. Arab leaders were keenly aware of this sentiment, and failing to intervene could have jeopardised their domestic standing. Yet, despite this public pressure, the intervention was marred by a lack of coordination and trust among Arab states. Competing interests and fragmented strategies undermined the effectiveness of their actions, leaving Palestinians without the unified support they needed.

Defending Genocide

Just days before the 2025 U.S. election, Bill Clinton revived the myth of Palestinian rejection with his own twist during his campaign speech for Kamala Harris in Muskegon Heights, Michigan. In his remarks, Clinton justified the Israeli government's actions in Gaza, blaming Palestinians for their own suffering. His argument could lead one to believe that Palestinians were not oppressed prior to the October 7 attack by Hamas, and that Israel’s actions were a reasonable response to Hamas’s actions. He even went so far as to absolve Israel of responsibility for the deaths of tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians, attributing them instead to Hamas’s influence.

Clinton also perpetuated the narrative that Palestinians, and specifically Yasser Arafat, were responsible for the failure of the two-state solution at the 2000 Camp David Summit. He deflected from Israel’s responsibility for the Nakba of 1948, suggesting that Zionist leaders like David Ben Gurion created “a garden in the desert,” in a very weird attempt to justify the violent displacement of half the Palestinian population.

His speech was not just a defense of Israel’s ongoing occupation but a distortion of history, designed to pander to voters while obscuring the truth of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. By echoing falsehoods about the past, Clinton sought to maintain the status quo, convincing voters that Harris was the better choice for Palestinians, even as she too backed the genocide in Gaza. This rhetoric, aimed at managing U.S. public opinion, which for the first time is turning critical towards Israel, ignores the ongoing injustice faced by Palestinians. We also see how many people in the supposed bastions of free speech in both the USA and Europe seem to abandon it when it becomes uncomfortable, showing their real core value: hypocrisy.

The “Missed” Opportunity

It’s time to move beyond the narrative of Palestinian rejection which we see attached to both the past and in more recent events, grounded as they are in deeply racist imagery of the savage Arabs. As for 1948, the idea that they “missed their chance” ignores the systemic imbalance of power and the deep inequities enshrined in the partition plan itself. If we are serious about understanding the roots of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we must approach its history with nuance and empathy. The truth is, Palestinians didn’t reject peace—they rejected a future built on injustice. And that distinction matters, now more than ever.

All articles on Diaspora Dialogue are free to read for one year from publication. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and would like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing, or by buying me a coffee. Thank you for reading and being part of the dialogue!

Very well articulated. Many thanks