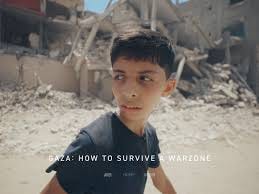

I’ve already written a review of the now-pulled BBC documentary “Gaza: How to survive a war zone”, , but I felt the need to return to it. This time, not just to reflect on the documentary itself, but to dig deeper into the controversy surrounding its removal — and the young boy at the heart of it. Consider this a review revisited.

But that honesty came at a price. After getting praise and positive reviews, the BBC suddenly took the documentary down from its iPlayer platform. Why? Because of claims that Abdullah’s father, Ayman al-Yazouri, works in the Hamas-run government in Gaza. The film, which gave a rare and human look at life in Gaza under attack, was now seen as a problem — not because anything in it was false, but because of who his father is.

In that moment, Abdullah went from being a narrator to being a target. Not just for critics, but also — indirectly — by the BBC itself. I hope though, even if I fear otherwise, not a target for IDF. Instead of standing by its film or supporting the people it featured, the BBC stayed silent and removed it. And by doing that, it said more about its own weakness than about Abdullah.

Why is there so much focus on Abdullah? Because the backlash was aimed at him. Gaza: How to Survive a Warzone follows several children and shows both joy and pain through their eyes. But it’s Abdullah’s voice that ties the story together. His words, his calmness, and his perfect English made people stop and listen — and that visibility is what made him a target. To understand the media’s reaction, we must understand what he represented and why it was so threatening to some.

Who Is Ayman al-Yazouri?

The reason given for pulling the documentary was that Abdullah’s father is linked to Hamas. But that claim doesn’t hold up under closer scrutiny. Ayman al-Yazouri is a technocrat — a deputy minister of agriculture. In Gaza, where Hamas runs the government, many professionals have no choice but to work within that system to keep everyday services going. Mixing up civil work with militant activity is misleading — it means Palestinians can’t even run basic services without being punished politically.

Would a child in the West be blamed for their parent’s government job? Would their story be dismissed, their voice questioned, just because of where their father works? Of course not. But Palestinians are held to a different standard.

Speaking English Is Not a Crime

Abdullah's ability to speak perfect English became another odd point of criticism. Some commentators used it to question his authenticity, suggesting he was coached or “too good to be true.” The idea that a Palestinian child could be articulate and fluent in English seemed to challenge what many expect of victims: they must be inarticulate to be believed.

This suspicion isn’t just insulting; it’s deeply revealing. When Palestinian voices sound too familiar, too fluent, too "Western," they stop being easy to denounce. They make people uncomfortable. They close the gap that allows audiences to watch suffering without confronting the full reality. And so, the very qualities that made Abdullah such a strong narrator were weaponized against him.

Western Media and the Palestinian Gaze

The BBC’s decision isn’t a one-off. It fits into a much broader pattern of media unease with Palestinian voices taking control of their own narrative, or having agency. When Palestinians speak, the instinct is often to question, explain, or dismiss what they say. They’re rarely treated as the primary source of their own stories. Instead, their experiences are filtered through foreign correspondents, military reports, and "balanced" commentary that tries to create parity between the occupier and the occupied.

Palestinian suffering is allowed to be told, even encouraged — as long as it remains abstract. But when it’s voiced clearly, by someone who might sound like our own children, who might show humour or pride, it becomes a political problem. The need to discredit their words becomes urgent.

The Real Harm: A Child Under Fire

Abdullah now faces the consequences of speaking out. He shared his truth, and for a moment, the world listened. But that moment was brief, and the world quickly turned its back. By questioning his credibility and amplifying unfounded accusations about his father, the BBC placed a target on a child already enduring unimaginable hardship. This wasn’t just an editorial mistake. It was a failure of ethics.

Journalism isn’t just about what is said; it’s about what is defended. In this case, the BBC chose to appease rather than stand firm. It could have clarified the father’s role, supported the film’s integrity, and protected the child it helped bring into the spotlight. Instead, it fanned the flames of a backlash driven by politics and fear.

Conclusion: Who Gets to Speak?

Gaza: How to Survive a Warzone is one of the most vital documentaries of our time. It shows war through the eyes of children, offering a deeply human perspective that cuts through the noise of statistics and propaganda. Abdullah’s voice deserved to be amplified, protected, and remembered. Instead, it was silenced by the very institution that gave it a platform.

The real question isn’t whether a boy should tell his story. It’s whether we’re willing to listen when he does—and whether our media will stand by him. The BBC failed that test. And in doing so, it reminded us that for Palestinians, telling your story can come at a dangerous cost.

All articles on Diaspora Dialogue are free to read for one year from publication. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and would like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing, or by buying me a coffee. Thank you for reading and being part of the dialogue!

The biggest fear for zionists is that people begin to see palestinians as humans. But the funny part is that so many people saw or began to see palestinians as humans. Meanwhile people begin to see israelis as evil, that is new and understandable. I for example didnt know that in thailand israelis began to harass the people over there. There are stories that israeli tourists dont or dont want to pay for the food they eat in restaurants etc and begin to steal property of thais. Like a bad comedy scetch. In thai shops u can find " no israeli allowed", well thats funny tbh 🤣